Butternut canker is a destructive fungal disease that threatens the long-term survival of butternut trees across North America. Caused by the pathogen Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum, it spreads rapidly through wounds in the bark, forming dark, sunken cankers that eventually girdle and kill the tree. This disease is especially harmful because butternut decline, tree cankers, fungal infection, walnut family trees, and forest health are all directly affected as the fungus weakens natural populations. Many woodlands have already experienced major losses, making early identification and proper management essential. Understanding how butternut canker develops, spreads, and impacts native ecosystems is the first step toward protecting these valuable hardwood trees.

What Is a Butternut Canker? (Complete Overview)

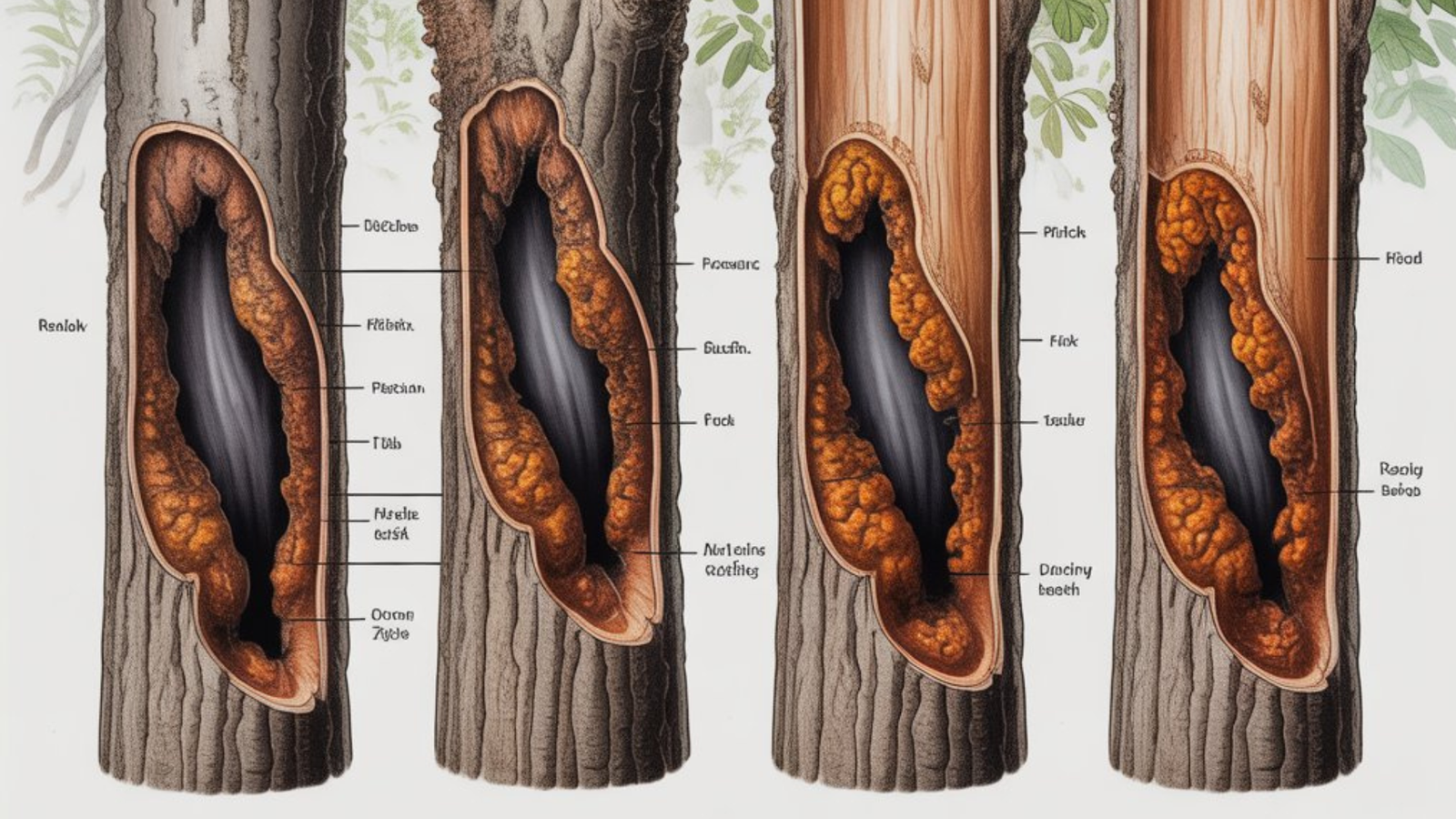

Butternut canker is a butternut canker disease caused by the fungus Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum. This organism triggers a severe butternut tree infection that forms dark wounds on branches and trunks. As the fungus grows, it creates black sunken canker patches that interrupt nutrient flow and weaken the entire tree. These wounds expand slowly at first but intensify as the fungus penetrates deeper layers of bark and wood. Because the infection spreads through surrounding forests, affected trees often decline faster than most homeowners expect.

The pathogen responsible for this infection attacks the inner bark, leading to canker appearance on bark that is easy to overlook in the early stages. Over time, the disease progresses and creates peeling surfaces, cracks, and a fluid discharge that signals deep damage. These conditions slow the tree’s ability to heal and increase vulnerability to secondary infections. The fungus can persist for many years, which complicates forest disease management efforts across the United States.

Origins of the Fungus and How It Spread

Scientists believe the fungus behind butternut canker arrived from an unknown region outside North America. Once it appeared on the continent, it spread rapidly through natural wind movement, animal activity, and environmental disturbances. Researchers traced early cases to the Upper Midwest, where forest stands showed sudden health declines and widespread losses. As the disease advanced, many areas reported rising butternut mortality rate concerns and unexplained bark damage.

Historical patterns show that pathogen spread through rain played a major role in early transmission. Raindrops carried spores down trunks and into fresh wounds, which accelerated the disease progression signs. In addition, insect-borne tree pathogens helped move the fungus between branches and neighboring trees. These factors allowed the disease to expand into large forest regions throughout the United States.

Host Species and Vulnerability of Butternut Trees

Butternut trees are especially vulnerable to this disease because their bark structure allows easier fungal penetration through wounds. Other Juglans species show more resistance, but butternut lacks protective defenses that can slow fungal growth. Once the infection begins, the tree struggles to seal the wounds, and its natural canker wound healing response becomes ineffective. Over time, the species became labeled as a butternut species at risk due to high losses.

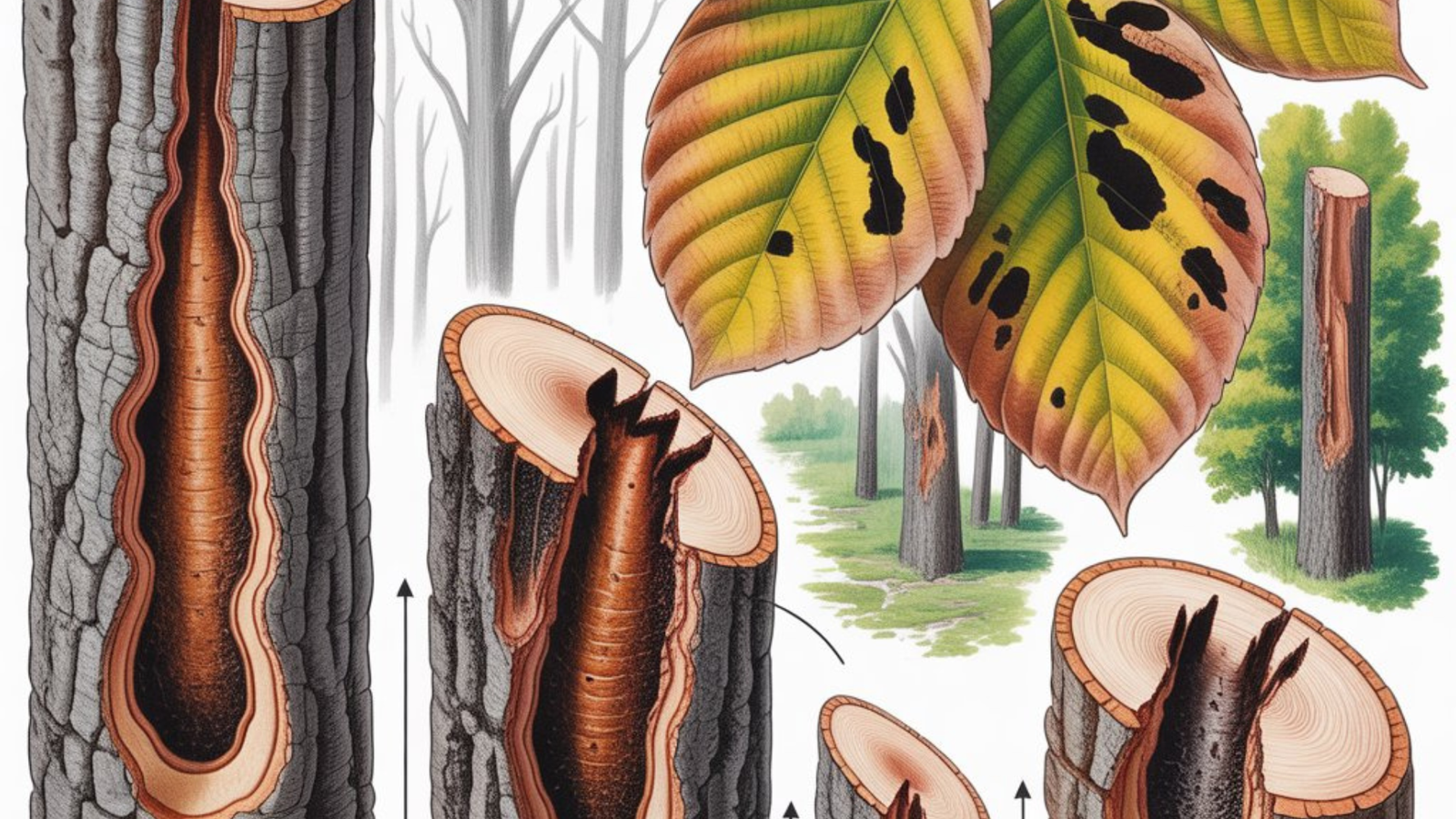

Because this tree serves wildlife and ecological roles, losing it harms forest diversity. Many American forests depend on butternut trees for shade, habitat, and food sources. When infection spreads, the tree’s weakened structure leads to crown dieback symptoms, bark deterioration, and poor growth. These changes make the species more vulnerable to weather stress and drought conditions.

Characteristics and Life Cycle of the Pathogen

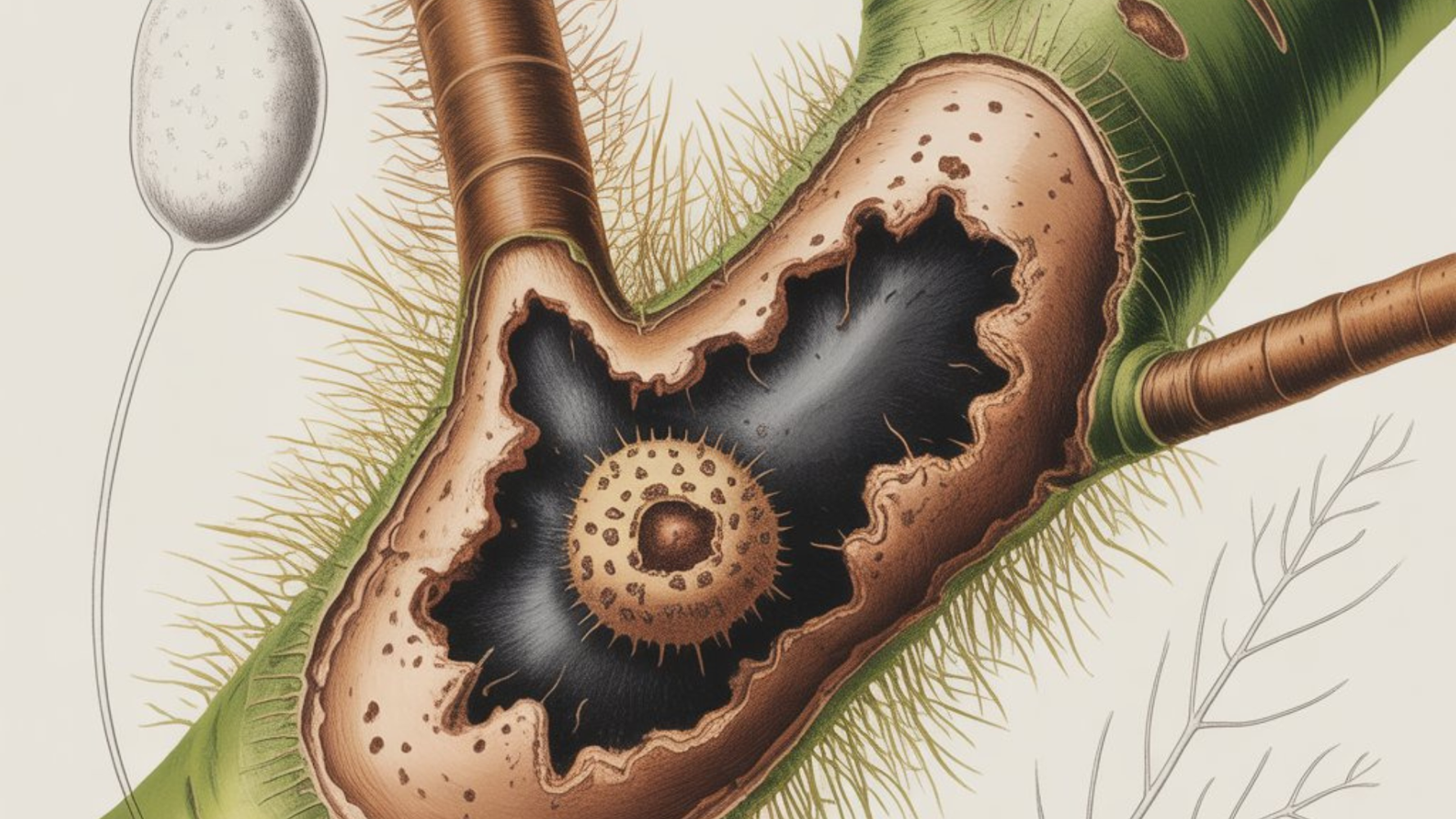

The fungus grows through multiple stages, beginning with spore release during warm, moist conditions. Spores settle on bark surfaces and enter through natural openings or storm-related wounds. Once inside, the pathogen creates twig and branch cankers that gradually expand. As the fungus matures, it forms new spore-producing structures that restart the cycle. These phases repeat throughout the year, especially in rainy seasons.

Environmental patterns influence the life cycle heavily. During wet weather, fungus spreading through rain moves spores downward along the trunk. When insects feed on bark or create small openings, they also enable easy spread of butternut canker. These combined pathways allow the disease to survive winter and reappear stronger in spring. Over time, tree defenses weaken and infection becomes more severe.

Early Signs, Symptoms, and Tree Damage

Early symptoms appear as shredded bark on trunk surfaces or small pits that seem harmless at first. These markings expand into elongated dark wounds that signal deeper internal decay. As the disease spreads, the tree loses vigor and develops crown damage percentage issues, meaning large portions of its upper canopy begin to fail. Under the bark, damaged tissues release a blackish fluid from infected bark when squeezed or exposed.

As the disease progresses, the bark may show a pale boundary known as a whitish margin around canker, which indicates fungal growth at the edges. Later stages produce dead branches, thinning crowns, and reduced leaf size. Because these signs appear slowly, many homeowners overlook the problem until significant damage occurs. Monitoring trees closely helps detect issues before the infection takes over.

How to Identify Butternut Canker on Branches, Trunk, and Crown

A reliable way to identify this disease is to examine the trunk for deep wounds or discolored patches. Many infected trees display tree trunk canker symptoms in irregular patterns along the bark. These wounds resist healing and often appear in clusters. When inspected closely, the bark may show peeling or cracking that exposes darker inner layers. These characteristics help distinguish this disease from other bark problems.

The crown also offers clear indicators. Trees suffering from infection present thinning foliage and sections of dead or weakened upper branches. These declining areas align with crown leafless percentage thresholds, which reveal how severely the disease has progressed. Because these symptoms connect directly to internal damage, recognizing them early improves your chances of effective treatment.

Impacts on Forests, Ecosystems, and Tree Survival

Butternut canker weakens entire ecosystems by reducing the number of healthy trees across American woodlands. When trees decline, wildlife lose food sources and habitat areas. As losses grow, overall forest stand management becomes more complicated. Landowners must adapt strategies to balance thinning patterns, species distribution, and restoration goals. These challenges intensify as the disease spreads into new regions.

The long-term threat extends beyond individual properties. Large-scale infections lead to higher butternut mortality rate concerns, forest instability, and disrupted nutrient cycles. As more trees fall, soil becomes exposed to erosion, and neighboring species struggle to fill gaps quickly. This creates lasting ecological imbalance and reduces resilience in local forests.

Best Practices to Manage and Control Butternut Canker

Effective management begins with thorough tree health assessment. Inspect trees for bark changes, cankers, and crown decline. When infections appear early, limited removal and high-value tree pruning may slow disease growth. Trees showing advanced symptoms require more serious intervention. Professionals often recommend strategic removals, especially when the trunk has large areas of damage. This prevents new infections from reaching nearby trees.

The table below summarizes recommended responses for different stages of infection.

| Tree Condition | Recommended Action |

|---|---|

| Small cankers and mild decline | Monitor, prune affected branches, support growth |

| Moderate cankers with crown thinning | Begin removal of infected butternut trees in clustered areas |

| Severe trunk damage | Remove immediately under removal criteria for infected trees |

| Valuable trees with minor wounds | Attempt canker wound healing response support and pruning |

Proper disposal of infected wood is essential to prevent further fungus transmission in forests. Leaving cut wood on the ground increases the risk of new infections around the property.

Long-Term Prevention and How to Avoid Future Problems

Prevention focuses on strengthening tree health and reducing infection pathways. Landowners often create stand openings for regeneration, which improve airflow and sunlight penetration. These conditions help young seedlings grow without excessive moisture around the bark. Healthy trees have stronger resistance and may slow fungal growth naturally. Encouraging diversity in forest stands also reduces overall vulnerability.

Another long-term method is applying proactive forest conservation guidelines. This includes monitoring rainfall patterns, managing storm damage quickly, and reducing insect injuries that open pathways for infection. When combined with regular inspections, these strategies reduce the risk of new wounds and improve resilience in aging trees.

Research-Backed Strategies From the Canadian Forest Service (CFS)

Although CFS researchers focus heavily on butternut decline in Canada, their findings provide valuable guidance for American forest managers. Their studies highlight the importance of identifying trees capable of resisting early infection. These trees often show smaller cankers, better bark structure, and consistent growth even during high disease pressure. Preserving these individuals helps maintain genetic diversity and supports natural resistance across forest systems.

CFS also recommends increasing regeneration efforts through seedling regeneration strategies. By planting young trees in managed areas, landowners can offset losses and create healthier future populations. Their research emphasizes quick removal of severely infected trees to slow forest transmission, a strategy that aligns well with U.S. woodland management practices.

Collaborative Actions and Conservation Efforts

Collaboration plays a vital role in protecting butternut trees across the United States. Government agencies, private landowners, and conservation groups work together to report infection patterns and develop new management tools. These networks help create updated management of diseased woodlots guidelines and promote awareness of treatment options. Sharing information across regions strengthens national response strategies.

Current conservation efforts also target species at risk protection initiatives. These programs encourage planting resistant trees, studying disease patterns, and restoring damaged woodlands. By coordinating efforts between state forestry departments and research institutions, communities can slow disease spread and preserve valuable natural resources.

Frequently Asked Questions About Butternut Canker

People often ask how quickly this disease spreads, and the answer varies by environment. Wet conditions, frequent storms, and insect activity speed up infection, especially when bark injuries appear. Another common question concerns treatment. While no cure exists, early pruning, careful monitoring, and removal of severely damaged trees protect remaining forests. Many homeowners also ask about diagnosis. Identifying canker appearance on bark and shredded bark on trunk helps confirm infections early.

Landowners also wonder whether chemical treatments work. At this time, no proven fungicides eliminate the pathogen completely. However, improving tree health encourages stronger defenses, which slows disease progression. Some people ask when to remove a tree. Professional assessments consider trunk circumference affected and overall vitality before recommending removal.

Conclusion

Butternut canker remains a significant threat to American forests, but informed management helps reduce losses. When you observe early symptoms, take action quickly to protect surrounding landscapes. Support regeneration, monitor weather-related wounds, and practice strong conservation methods. By understanding disease behavior and applying smart interventions, you can help preserve butternut trees for future generations.